What follows is an excerpt from my first book with The Professional Citizen Project called CM-9 Adverse Conditions and Environments (ACE). I'm a firm believer in the 10 Essentials and make sure to use them as the base of not only my physical kit, but as a base in my skill sets of survival in the outdoors.

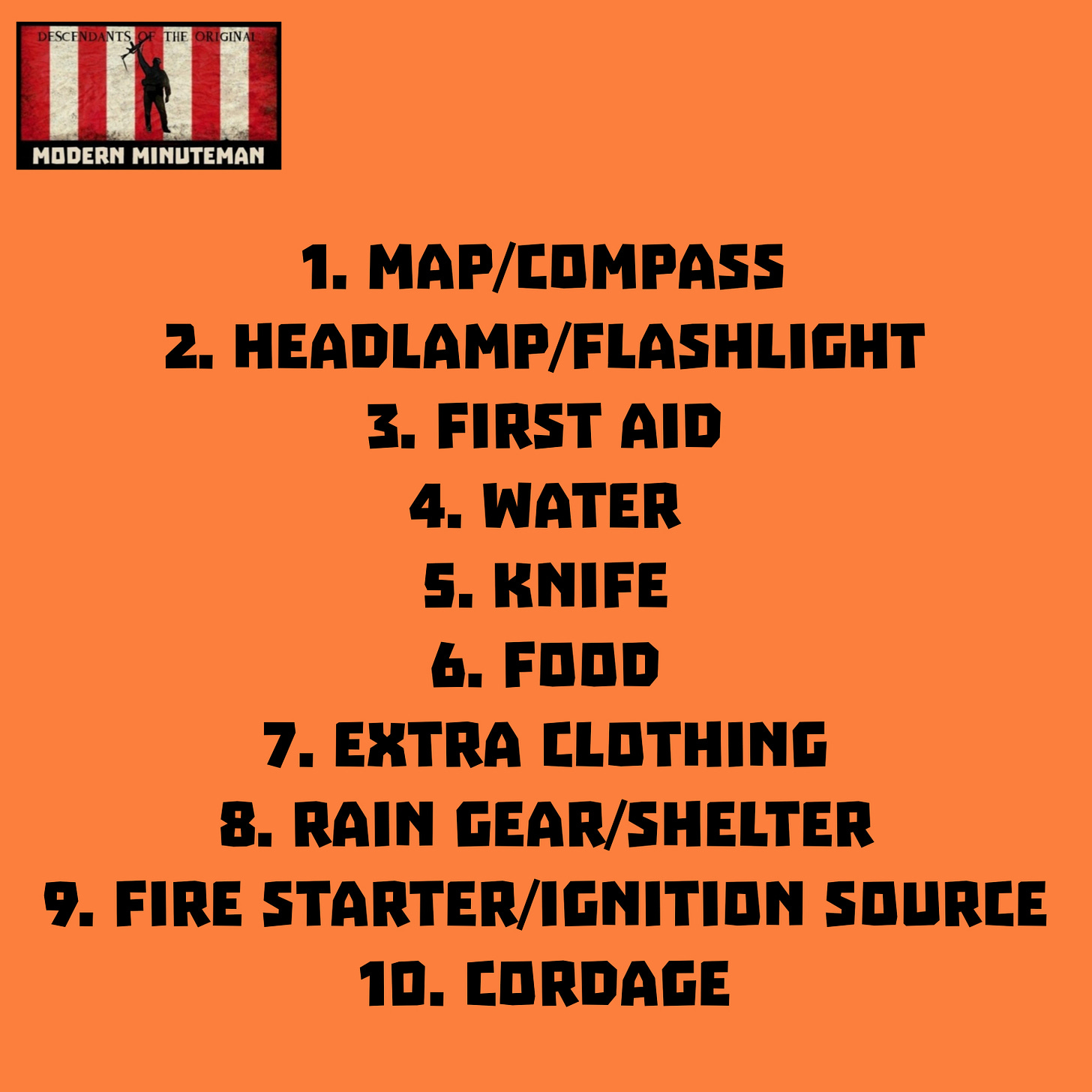

The 10 Essentials:

The special items that the Professional Citizen should always have in their kit has become known as the “Ten Essentials” This was put together many years ago in the mountain community as a way of identifying 10 important items to always have with you (or on you). There have been many variations of this list over the years and here we will identify and describe each one in more detail.

1. Map/Compass

Not all who wander are lost, right? It's been a popular saying for years for outdoor enthusiasts around the country. But have you ever been lost? I mean really lost as in you have no idea where you are. I got lost for a day in the Uinta Mountain Range in Northern Utah on a solo backpacking trip. Wasted an entire day because I thought I knew where I was headed after breaking camp and didn't bother to check myself first with my map and compass.

Map and compass use is one of the most overlooked skill sets and a perishable one as well if not regularly practiced. Today we have GPS, cell phones, downloadable maps, etc but those don't mean anything if you don't know the basics of navigation. How to orient a map, triangulate to find your position, plot a course, use waypoints, take a bearing, shoot an azimuth, pace count, read a map, and more. These are the basics that every Scout and Scouter should know and practice with. GPS batteries can die, cell phones lose service and die, downloadable maps rely on batteries that, well die... You see the trend when you depend on technology to make up for lack of basic skills....

So, what should a basic navigation kit consist of? For every Scouts daypack a compass with rotating bezel and clear base plate and a map of the area they are in. The compass should have a lanyard for keeping around their neck and the map should be waterproofed by laminating, in a map case, or in a zip lock bag.

What are some additional tools to go with your map and compass?

*Ranger Beads or pace beads for measuring the distance traveled

*Small write in the rain notebook/writing utensil for writing down bearings, distances, rotating landmarks/places of interest, leaving notes for others, etc

*Red light for navigating at night. Red light helps with maintaining good night vision and helps contour lines pop on a map in the dark. A white light can wash them out.

*Ruler/protractor, or string for measuring distances, marking grid coordinates, or for plotting course on a map. Most compasses also have a measuring scale on the sides that can also be used for this purpose.

Navigation can be a deep rabbit hole to go down, but the basics are simple, and everyone should know them. Technology is nice as an aid, but nothing beats knowing the fundamentals first.

2. Headlamp/Flashlight

Even if you have no intention of being out after the sun goes down it is essential to carry a light source. Light is essential for many reasons. It helps us find our way at night, helps with nighttime camp activities, can be used to aid in navigation, signaling for help or rescue, light can also be used as a friend/foe identifier.

Light can come from many sources including flashlights, headlamps, glow sticks, strobe lights, fire, and more.

-Headlamps: hands free light makes hiking and camp chores easier by freeing up your hands. They usually have an adjustable elastic head band and a tilt housing for the light itself.

-Handheld Flashlights: by far the most common lights out there. From tiny keychain lights to large work lights. Many handhelds have a pocket clip for carrying in your pocket and have either a tail cap button or side button.

-Hat Clip Lights: these lights are like a small handheld but with a clip for attaching to a baseball bat bill.

-Glow sticks/Chem lights: great secondary light source for area marking, tents, emergency lighting, making buzzsaws for signaling, and more. Hang one on the latrine at night for easy identification. Use different colors for playing capture the flag at night or for orienteering courses.

-Weapon lights: I'm a believer that every rifle should have a light on it (a sling too). Depending on your grip and setup you can either have a pressure pad switch or a press button setup. Learn how to properly use a weapons light.

-Rescue Strobes/Beacons: these specialty lights have been used by backcountry users and the military for years. They can be seen miles away and are designed to run for multiple days. They are also useful for nighttime bike rides for safety. Some models will flash SOS and others have an IR (infrared) feature for use under night vision devices.

The last point of consideration is the power source for your light. Standard batteries are the most common, but you need to bring spare batteries. Rechargeable lights are becoming more common but still require a power source to charge from which means bringing along some sort of battery bank to plug into.

Furthermore, lights with a red lens option help with preserving your natural night vision and, in some uses, can keep your light signature down when you aren’t wanting to be found. Don’t forget spare batteries or charging options when choosing a light.

Finally, learn proper light discipline and practice it.

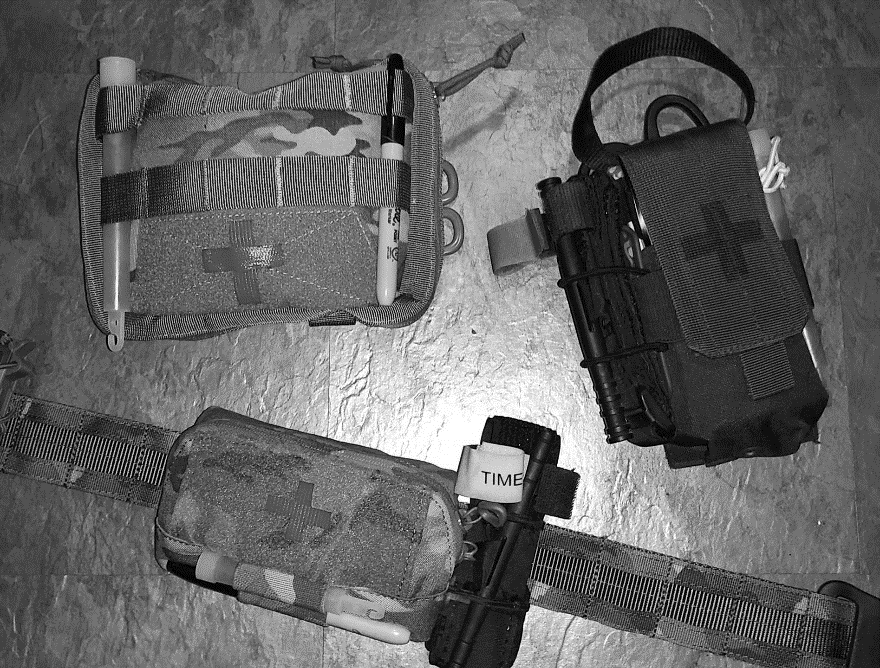

3. First Aid

The very nature of working in the outdoors, especially for the Professional Citizen, operating under distress, with heavy loads, various environments, working with sharp objects and things that create holes, makes it essential to have a first aid kit and the training to use it. Think about the activities we undertake, and the inherent dangers associated with them.

First Aid is one of the most overlooked of all the essentials. Folks like talking about all the gear like tents, packs, stoves, and more but when the discussion turns to First Aid then the conversation starts to fade away. I think it's because of the lack of training in the community. We are all always one step, one swing of an axe, one slip of a pocketknife, one spill of boiling water, one mishap around a firepit, one accidental discharge on the range from a bad accident but most people's First Aid kits are severely lacking to treat an injury beyond a scrape or booboo and worst yet is their training is at a level to put a Band-Aid on. These are hard truths, but we really need to look at First Aid in a more serious light.

First off, GET TRAINING!!! Red Cross 1st aid and CPR are not enough for what we do in the woods. At a minimum take a Wilderness First Aid class. Make sure it is a class that conducts scenario-based training in the field and makes you use your own kit. Take a Stop the Bleed course. This isn't just for an active shooter situation but also for major hemorrhaging from axe and knife injuries. These 2 classes should be minimum training for everyone. If you want to go beyond then take a Wilderness First Responder course, EMT basic training, or take a TECC (civilian equivalent of the military Tactical Combat Casualty Care course).

Secondly, your First Aid kit should represent the level of care you are trained to administer. Chest seals, tourniquets, and pressure bandages are just stuff if you don't know how to properly use them. Most common injuries are scrapes and bruises that are easily treated with a Band-Aid or two and some antibiotic ointment. Some injuries like sprains may require an Ace bandage. Think of the environmental factors as well when putting together your First Aid kit. Think of putting a package of antacids, like Tums, for upset stomachs and oral hydration salts in cases of dehydration. Pro tip: rolled gauze and tape will do wonders and cover most bleeding injuries, pack lots of rolled gauze.

-Booboo kits... I'm a big fan of a simple booboo kit that should be in every Scouts pack. A booboo kit is exactly as it says, it treats booboos. Bandaids, moleskin, antibiotic ointment, and tape about covers it. They fit easily in a cargo pocket so it’s always on your person. Make them at troop/den meetings so everyone has their own!

-Trauma kits... This is separate from a "Booboo" kit in that it has the necessary items for dealing with massive hemorrhaging, airways, and broken bones. Tourniquets, Nasopharyngeal Airway Device (NPA), pressure dressing like Israeli bandages, SAM Splints, and so on and so forth are necessary for trauma in the field. If you are in the backcountry and hours (maybe days) away from that next level of care you, as a leader, need to have the ability to treat and stabilize that injury while you either wait for help or you are in a situation where you need to prepare to move the injured to an area that is safe and accessible to rescuers. This is big and why it is so important to seek the advanced training mentioned above.

Other considerations are things like TCCC casualty cards, trauma shears, markers, light sticks, wet wipes, nitrile gloves, space blankets, and more.

I could really go on and on, but I think we get the point on the importance of a proper First Aid kit and being trained in its use. If you haven’t had any training, go get it now.

More details on first aid will be in Chapter 2.

4. Water

Water is one of the top 3 survival priorities so it should come as no surprise to see water on this list. The means to carry water and procure/treat it are always essential.

Good old high-quality H2O. You need water, without it you will die. Plain and simple. There's a reason it's one of the top three survival priorities. There is a thing called the rule of 3's, that you can survive without food for 3 weeks, without water for 3 days, and without air for 3 minutes. That's how important water is.

Before heading out it is important to fill up or top off your water bottles. I prefer carrying 2-1-liter bottles (I like having a metal nesting cup (like the Toaks Titanium cups) for a Nalgene or a canteen cup for a USGI water bottle, having a metal container will be important if you need to boil water to purify it) for regular camping and I'll add a 3-liter hydration bladder for backpacking and longer day hikes.

In most environments, you need to have the ability to treat water by filtering (like a Katadyn Hiker or Sawyer Mini), purifying using chemical tablets or drops (iodine or chlorine tablets), or boiling from rivers, streams, lakes, and other sources. Getting sick from drinking untreated water is a very real thing and it will take you out of the game quickly, don't do it. In cold/snowy environments you will need a stove, fuel, pot, and lighter to melt snow.

Daily water consumption will vary from person to person. For most people, 2 to 3 liters of water per day is usually sufficient, but in hot weather or at higher altitudes, 6 liters may not be enough. Plan for enough water to accommodate additional requirements due to heat, cold, altitude, exertion, or emergency.

5. Knife

Who likes knives? Probably one of, if not the most, useful tools one can carry! You can use a knife to help with food prep, process firewood and kindling, make other tools with it, cut cordage, make fire, help create shelter, repair gear, make traps to catch food, and more.

So, what kind of knives are there? Classic Swiss Army Knives (SAK), old jack knives, multitools, clip folders, fixed blade knives, etc. There are a lot of knives in the marketplace for outdoor use but what is best for you? Let's cover 3 popular ones.

-Swiss Army Knives: Originally commissioned in the late 1800's, this is a classic Scout knife. Typically you have a small and large folding blade, screwdriver, can opener and bottle opener, tweezers and a toothpick and a leather awl punch. Easy to carry in a pocket or have a lanyard attached to it. Normally a Scouts first knife is a SAK. Great for basic camp chores like food prep, cutting cordage, and making feather sticks or shavings for starting fires.

-Multitools: Really an upgrade from your classic SAK's in terms of utility. Usually has a single blade, a small saw, multiple screwdrivers, can/bottle openers, awl punch, and built in pliers and wire cutters. Like the SAK it is great for camp chores, cutting cordage, and basic fire prep but also is good with field repairs on gear, the pliers are nice for bending wire or metal for trap and snare making or for fashioning fishhooks from metal. The saw helps with cutting notches for making camp tools and traps.

-Fixed Blade camp knives: There's a reason Jim Bowie carried a big knife. He was a master frontiersman who lived off the land, wrestled a bear, and ventured into the unknown. He needed a knife to handle it all. Fixed blade knife (something with a 3-to-5-inch blade for scout use) can do lot. Some look at them as being unwieldy due to the larger size versus a SAK but when used right are more stable and safer. You can baton wood (batoning wood is the act of splitting a larger diameter piece of wood into smaller pieces using your knife or axe), the weight makes creating feather sticks and shavings easier for fire making, making camp tools and furniture becomes easier, and more...

I'm a believer in carrying 2 knives... A small everyday knife like a SAK for in the moment use and a fixed blade for camp chores and harder work. One in the pocket and one on the belt.

The last point on knives is the way we view and teach their use. We need to do a better job of how we view knives. They are tools, nothing more, nothing less. You cut food and rope with them, you create tools and shelter with them. You can make fire to cook and keep warm with them. You can make camp projects like tripods, chairs, cook stations, tables, and more with them.

6. Food

A one-day supply of food is reasonable to keep in one’s base kit. Mr. Murphy is always waiting just around the corner to foul up your well-intentioned plans. Weather delays, faulty navigation, washed out trails, injury, and so many other things can cause your 5-hour outing into an unplanned overnighter and longer.

The general rule of thumb is for a day hike to carry a full days’ worth of food and on a multi-day trip to pack for as many days as you plan on plus an extra days’ worth in case your trek gets set back due to weather, injury, navigation issues, and so on and so forth.

For the type of food, well that gets interesting. My own preference is for easy to eat items that can be carried in my pockets that are high in carbs, protein, and sugars with some salt. This mixture gives you a good mix of energy and electrolytes replacement. So, I like granola bars, beef jerky, hard candies, and dried fruit/nut mixes. For a day hike this works perfect.

Normally, on a multi-day trip my breakfast is simple with a granola bar and a cup of instant coffee, lunch I like to just snack all day on jerky and dried fruits and nuts while on the move, and for dinner I like an easy hot meal like Raman with tuna, chicken, or summer sausage added to it. It's easy, quick, filling, and quick to clean up. This type of menu packs well, requires minimal heating from a small stove, and is lightweight with little waste. I will usually use one water bottle for powdered drink mixes like lemonade.

For the last few years I've been pre-making ration packs for sustainment kits that are easy to pack. Each ration pack contains approximately 2200 calories including proteins, fats, carbs, sugars, and vitamins. 2 of them fit in a pocket on an Alice pack (similar to broken down MRE's for those of you who know) or 3 will fit in a Bergen pocket, once again if you know, you know... If you're going on a day hike toss one in your pack. Going on an overnighter or weekend trip then toss a few more in. The freezer size zip lock bag doubles as a bag for your trash. Bonus is I keep an extra freezer zip lock bag in the ration kit to use for water collection in a survival situation.

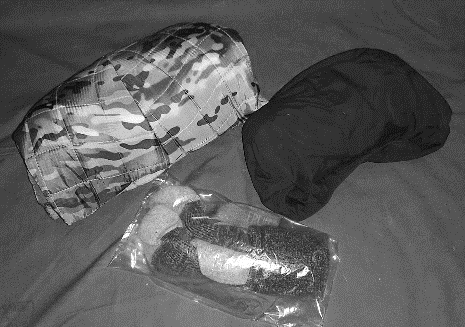

7. Extra Clothing

The term “extra clothes” refers to, beyond the clothes on your body, additional layers that would be needed to not just accommodate changing weather conditions, but to survive the long and inactive hours of an unplanned overnighter. So, to begin with you need to ask yourself what extra clothes are needed to survive the night in my emergency shelter in the worst conditions that could realistically be encountered on any given trip?

But let’s start with some basics for clothing as it is listed in the traditional 10 Essentials… At a minimum in my day pack, I'll carry a spare pair of wool hiking socks, a light insulating layer, and appropriate rain gear. If your socks get damp, you have a spare pair to change into. If you get chilled you have something to put on to warm up with, and if it starts to rain you have something to stay dry in. Seems pretty simple right. But to better understand the notion of “extra clothes” we should probably have a better understanding of the layering system as a whole which we will dive into later in this book.

8. Rain Gear/Shelter

Rain gear... A crucial piece of gear that seemingly gets placed low on many folk’s essentials list. We covered extra clothing in a prior post and the importance of staying dry, but yet many still fail to plan for rain. Or if they do, they place their bets on a $1 see through plastic poncho that they sell at Sea World for when Shamu splashes you to stay dry. But it rips the first time they put it on and then look silly standing there soaking wet anyways. Sorry, that just bugs me.

So anyways, proper rain gear is a necessity if you are venturing into the outdoors. For hiking, backpacking, and camping a well-made rain jacket will keep you dry in the hardest of downpours while also being lightweight and packable when stowed in your pack. Things to look for when buying a good rain jacket are taped seams, adjustable hood, and easily accessible pockets. Pit zips would be a bonus for increased ventilation. Also make sure it's sized large enough to fit over top of an insulating layer.

Another option that is gaining popularity again (and for good reasons) is your classic military ponchos. They are waterproof, small packing, easy to put on/take off, can double was an emergency shelter AND combined with a Woobie can make a lightweight sleeping bag.

Bonus uses for a poncho is being able to set it up during the day to create shade from the sun, make a rain catchment system with it, make an improvised litter, create an improvised pack raft for deep water crossings, makeshift sail on a canoe trip, and more. A military style poncho sounds pretty handy for outdoors use and deserves a spot in the ten essentials list.

It is too versatile a piece of kit to not be included.

9. Fire Starter/Ignition Source

Fire and the ability to make a fire, even in horrible conditions, is one of the big 3 survival priorities (fire, shelter, water). This is why it is included in our 10 essentials list. Having a solid fire kit (and knowing how to use it) in your pack is key to being able to reliably make a fire when it counts most. You and your mates are off exploring and one of you falls into icy water. You have to be able to make a fire NOW. Can You? Do you have the tools to do so? This is why we need a fire kit. With fire you can stay warm, purify water, signal for help, stay safe from predators, cook food, lift morale, see in the dark, and be the envy of your fellow outdoorsmen.

My rule of thumb is to have 3 different ignition sources and 3 different tinder sources.

My ignition sources:

-Lighter wrapped in duct tape

-Lifeboat matches with striker

-Ferro rod with striker

My tinder sources:

-Petroleum coated cotton balls in a metal tin

-Fatwood

-Wetfire fire starters

I also keep a couple small tealight candles for extending a flame or emergency light.

The duct tape on the lighter can extend a flame for several minutes which is useful for making fires in wet conditions. The metal tin can be used for making char cloth or for using as a dry surface for tinder bundles. Fatwood can be scrapped off and put into larger tinder bundles for lighting with a Ferro rod. The resin in the fatwood catches a spark easily and will hold a flame for a few minutes.

The goal with your fire kit should be to make a fire in any situation at any time. Just remember fire prep and practice is just as important which we will cover later in this book!

The ability to make fire is a skill set that requires constant practice. Fire can provide warmth, safety, signaling, the means to purify water, cook food, and much more.

10. Cordage

Have you ever broken a boot lace on a hiking trip? Ever had a pack strap break? Wish you had a clothesline to dry your gear on? Well cordage can help with those things and more. Keep a 25-to-50-foot hank of it in your day pack.

Cordage comes in all sizes, materials, and strengths.

-Jute twine is common at camp for lashing projects and when fluffed up can be used for fire starting. Usually, a 25 to 50 pound working load at best.

-Paracord (known as 550 cord) is probably the most common type of cordage due to its versatility and strength. Great for boot laces, lashings, tie outs on tarps/tents, ridgelines, clotheslines, lanyards, handle wraps, craft projects and more. Real paracord with the individual inner strands can hold 550 lbs. Hence the name 550 cord.

-Dyneema cord has gained popularity in the ultra-lightweight crowd for its small size and strong weight. It's pricey but can do most of what paracord will do. Some knots do slip through it. The thinner versions as shown have a breaking strength of around 1500 lbs.

-Braided paracord is regular paracord but 3 strands of it are braided together to create a stronger/thicker line for ridgelines or hoists. By braiding 3 lines together the working load increases dramatically.

-Dynamic rope is typically used for climbing. It is designed with a bit of stretch to help absorb the shock of as fall. These ropes go through special certification processes in the US and in Europe to be approved for use and have manufacture dates on them.

-Sisal rope is made of natural fibers and has great gripping and knotting strength that will not stretch when wet. Great for tying down loads and gear. Working load is about 250 lbs.

-Natural cordage can be made from vines, grasses, inner tree bark, and more. Twisting and braiding pieces together can make strong cordage like native peoples did.

Now for the bad news... Rope work is another "skill" that isn't paid enough attention to either. Knots and lashings are a cornerstone of any outdoorsman’s skill set. Time to get creative again with knots and lashings.

Great tips. A couple thoughts on the fire kit: I carry a couple of those "trick" birthday candles that don't go out when you blow on them and a few regular birthday candles that I'm willing to sacrifice if I'm trying to get a fire in wet conditions. They take up very little space in my fire kit and they give me peace of mind knowing I have one more tool as a backup. It doesn't hurt to have a couple lighters scattered throughout your gear. One in your pocket, one in your fire kit and another one in your cook set. Just my two cents worth.

#1 is a firearm with a shit load of ammo. I will come and take your shit because you didn't have firearm on your list. But I will leave you the first aid kit for your leg after I shoot you.